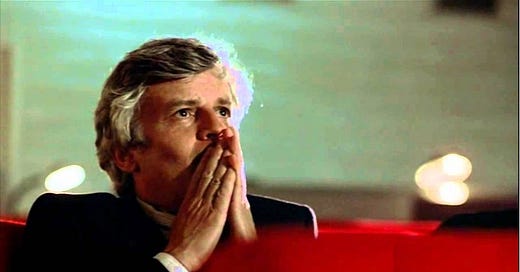

Jacques Perrin (Salvatore) watches a compilation of clips bequeathed to him by his father figure, Alfredo, at the end of Cinema Paradiso (directed by Giuseppe Tornatore), 1988

My son absolutely loves movies. They have helped him through difficult times. Now they are a bond between us. He bought us a BluRay player so we could watch some of the ones that meant the most to him. Many of my best conversations with him have been about films. He is very knowledgeable and can analyse any movie, knowing all the tricks a great director has up their sleeve to convince us that what we are watching is real. This used to bother me a bit. Surely it would undermine the magic?

But the creation of pretty much any art form involves an illusion that we can control life, that it is less chaotic than the reality. In The Fabelmans, Steven Spielberg’s semi-autographical portrait of his early years, there’s a memorable scene where the young Sam (SS’s alter ego) listens to his parents telling their kids they are getting a divorce. Suddenly the camera’s gaze shifts and we see a mirror image of Sam filming the whole thing. How could anybody do that, we might think? It’s inhuman, why isn’t he reacting to it, why isn’t he falling apart? But I think what that scene tells us is that this is the way Sam, and Spielberg, have made sense of reality ever since they were old enough to realise it’s as much an illusion as anything else.

In Sam’s case this happened the first time his parents took him to the movies, back in 1952. He was overwhelmed by the train wreck scene in Cecil B deMille’s The Greatest Show On Earth (could any title convey the concept of illusion better than that?) As a six year old boy, he literally dreamed about it, set up his new train set in the family workshop where his dad repaired TVs, and smashed the train up trying to recreate it. He needed to take things apart to figure out how they worked. But think of anyone who has devoted his life to creating cinematic magic, and you may well think of Steven Spielberg. Looking under the hood doesn’t always ruin the illusion. My 4 year old grand-daughter does her hardest work while she’s playing.

These are complicated ideas to express, and I tried to write a long, academic essay about them the day after I’d watched The Fabelmans. I did the same thing after my son and I watched a film that made me emotional, and him analytical - or was it really quite as simple as that? In both cases, the essay didn’t quite capture what I was trying to say. I’m sure Steven Spielberg feels that way sometimes about his movies, even the ones he won awards for.

Enough, already. I haven’t written a poem about The Fabelmans yet. Perhaps I never will. But here’s the other one:

WATCHING CINEMA PARADISO WITH MY SON I chose the best seat for your coming of age, right in the middle, just two rows back, but it turned out still to be too close for me to get a proper view I tended not to ask, once you had left what you were going through The most dangerous times were the ones when I thought I had the answer, or at least a good quotation. Maybe, once or twice, it helped, Most of us like to believe that sometimes the universe has mail for us. I think that’s one reason we all love the movies, it gives us a dark space to work on our stories rejecting the rushes that have a bad habit of catching alight To get to the ending that feels right takes visions bigger than our own. Sometimes it scares me to watch films like this, that lay everything out on the table, and stand by to watch me tearing up. Of course, you analyse each frame, you know the beats, and how they work, how they manage to make things more real than the real, but enough remains of the honesty of fantasy and privacy of dreams, to keep me wide awake the night before you take your homeward train and wonder whether it’s okay to let Morricone settle the score and pretend it’s lived experience, because it feels so good that way. You will always control what you want me to see, and that’s the way it needs to be, but in the end, what hits the cutting room floor has an audience of one.